Labour's internal war can only keep David Cameron smiling in the year ahead

Inside Westminster: Labour must pull itself together, as it is the only vehicle to block the road to a virtual one-party state

At a Christmas party held for Westminster journalists, Jeremy Corbyn joked: “As you know, I was absolutely the popular choice in the Parliamentary Labour Party.” He got a big laugh because fewer than 20 of his 232 MPs voted for him in the Labour leadership election in September.

It was a surreal occasion – the veteran left-winger serving wine and beer to reporters who had largely ignored him during his 32 years in Parliament and had not written many nice things about him in his first three months as leader. The event was “your and my worst nightmare”, Mr Corbyn quipped. He admitted he had never expected to become the first man to go from “the frozen wastes of the PLP backbenches to make his first appearance at the despatch box as Leader of the Opposition”.

Indeed, Mr Corbyn’s election was the most remarkable event in a memorable year, and has more long-term significance for British politics than David Cameron’s unexpected general election victory on 7 May. Until the exit poll bombshell dropped at 10pm, Labour was confident of forming a “lock-out majority” in the Commons to prise Mr Cameron out of Downing Street. That “majority” included the Scottish National Party’s MPs, confirming Tory claims that, despite Mr Miliband’s half-denials, Labour would do a deal with the SNP in the widely expected hung parliament.

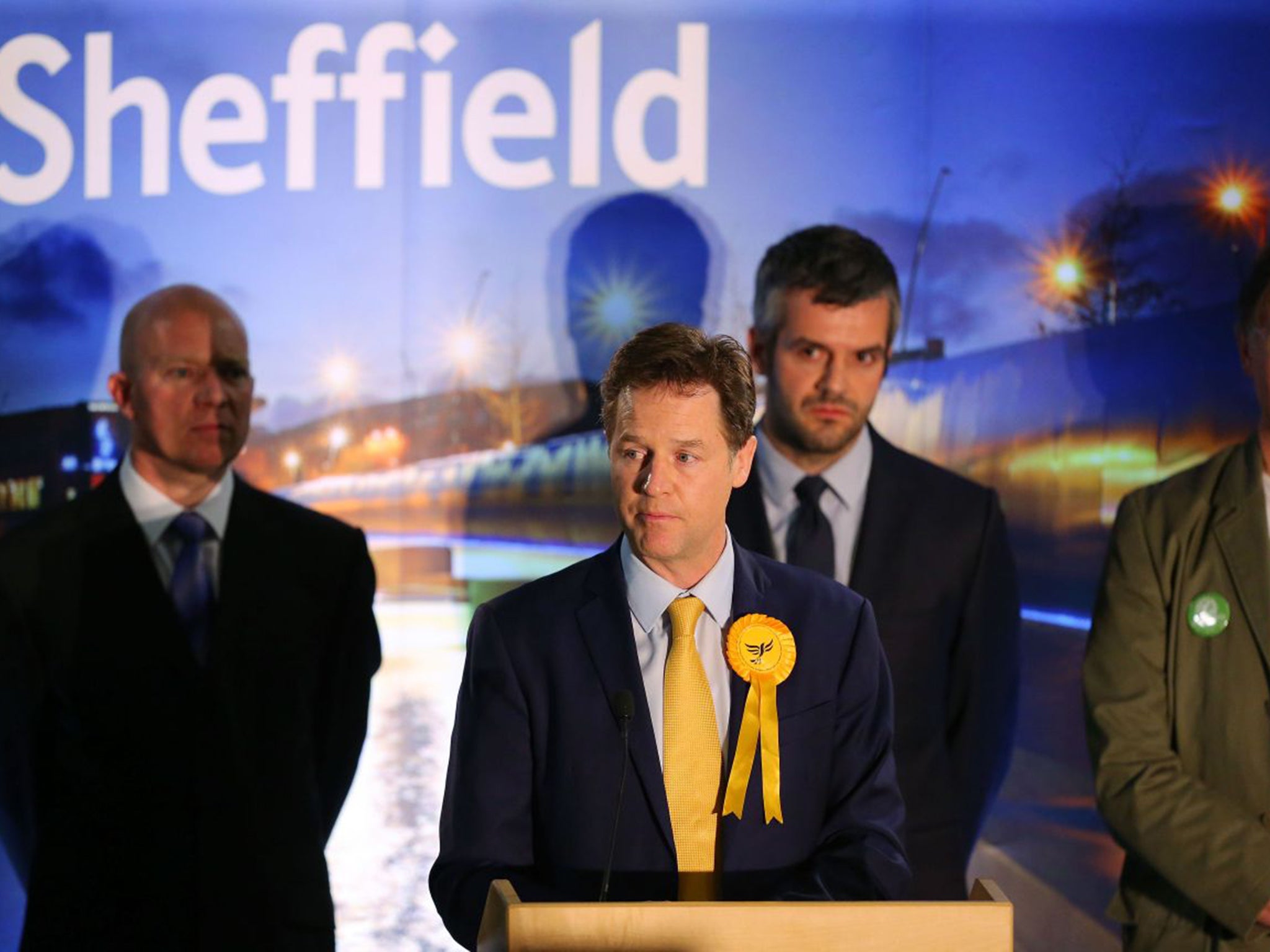

The voters in England sensed it and did not want it. The election result, although a personal triumph for Mr Cameron, was a vote against a Labour-SNP pact rather than a wholesale endorsement of the Tories. The same fears helped the Tories vaporise the Liberal Democrats. They underestimated the ruthlessness of their coalition “partners”, who gobbled up their South-west seats. I doubt we will see another one for a generation.

Mr Cameron seized his moment to hail the Tories as the “party of working people”. As Labour lurched left, the Prime Minister colonised the centre ground by adopting the goal of “real equality”.

In another year, the SNP’s rout of Labour would have been the most remarkable event. Its MPs have made a real mark at Westminster. Its iron discipline is forged by a single overriding goal. If Labour could be as united in opposition to the Tories, it would be in much better shape.

Instead, Labour has become two parties. Most of its MPs do not believe Mr Corbyn can win the 2020 general election and want to topple him before then, but he has the strong backing of the party’s members. At a friend’s pre-Christmas party, I chatted to a group of six long-standing grass-roots Labour members. None of them voted for Mr Corbyn, but all felt strongly that his MPs should respect his mandate and stop plotting against him. They all said that if Mr Corbyn stood down, John McDonnell, his close ally and shadow Chancellor, would be elected as his successor.

The Labour leader, unused to the burdens and pressures of office, had a shambolic start but ends 2015 in a much stronger position. Labour’s big win in the Oldham West and Royton by-election deflated his internal critics. His team believes the PLP is finally moving his way.

His enemies within may attempt a coup if Labour does badly at next May’s elections for the Scottish Parliament, local authorities and London Mayor. But they lack a single credible candidate and are in despair. One Blairite MP describes his soulmates wandering around Westminster like “the living dead”. Indeed, Mr Corbyn’s election was the way the party finally buried New Labour.

A big question for 2016 is whether Labour’s two tribes can meet in the middle. I hope they do, but doubt they will. A key test for Mr Corbyn will be whether he sacks or demotes Shadow Cabinet members who stood up to him over air strikes against Isis in Syria. That would hardly be the inclusive leadership he promised.

Another challenge is to reach out beyond the 250,000 people who voted for him in the Labour leadership contest, who comprise a mere 0.55 per cent of the electorate. Key tests for his critics will be whether some refuseniks agree to rejoin the frontbench team and accept that he will lead the party at the 2020 election.

Although Michael Heseltine raises the prospect of a Tory “civil war” over Europe, the media will focus on the one already raging inside Labour. One ominous sign is that the Labour left, more interested in retaining power in the party than winning it in the country, seems to hate the Labour right more than it hates the Tories.

Labour cannot rely on a Tory implosion over Europe. Already Tory minds plan how to heal the wounds after the referendum expected next summer. A global downturn on the Tories’ watch might tarnish the party’s economic credibility and create a platform for Mr Corbyn’s anti-austerity pitch – eclipsed so far by foreign and national security issues. But if they do not trust Labour on the economy, voters might hold on to the nurse for fear of something worse.

A Labour Party that is doing the splits needs to somehow pull itself together, as it is the only vehicle that can block the road to a virtual one-party state. Despite their very real strains over Europe, the Conservatives enter the new year with by far the best prospect of having a happy 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments