Stargazing in June: The lowest full Moon in 18 years

Watch out this month for a Full Moon that barely skims the horizon, a phenomenon that inspired prehistoric astronomers, Nigel Henbest writes

What can be more romantic than the "Moon in June," with couples promenading on a warm summer’s night under a huge bright full Moon hanging low in the sky? And in 2025, the Moon seems lower and bigger than ever.

In fact, the full Moon on the night of 10 to 11 June rises only 10 degrees in the sky (the size of your fist held at arm’s length) as seen from the latitude of London, Cardiff or Cork. If you are in Shetland, the Moon’s maximum altitude is only a finger’s width above the horizon. And it will be over 18 years until we witness such a low Full Moon again.

So, what’s going on? The place to start is with the Sun, rather than the Moon. Every year, the Sun follows the same path through the sky, known as the ecliptic (it’s the dashed line on the starchart). The ecliptic passes through the familiar constellations of the zodiac, from Aries through to Pisces. At the beginning of June, the Sun lies in Taurus (I know that’s not what the astrologers say, but the zodiacal signs have all shifted since Western astrology was first devised). Around Midsummer’s Day, the Sun crosses into Gemini, where the ecliptic is highest in the sky.

The Moon follows roughly the same path but much more rapidly, passing through all the signs of the zodiac in month. As it travels, the Moon’s shape – or phase – alters as different amounts of its surface are lit up by the Sun’s rays. When our lunar companion is completely illuminated – the full Moon each month – it always lies opposite to the Sun.

So the full Moon in June is 180 degrees around the ecliptic from the midsummer Sun, putting it firmly in Sagittarius – the lowest zodiacal constellation – and that’s why the Midsummer Full Moon always hugs the horizon.

If the Moon followed exactly the same path as the Sun, that would be it: repeat recipe every year, end of story.

But the Moon’s orbit around the Earth is tipped up, by about five degrees. As a result, it appears to travel alternatively above and below the Sun’s path. To muddy the plot further, the Moon’s orbit is swinging around in space, so the points where it’s furthest above or below the ecliptic gradually move around the sky, over a period of 18.6 years.

This year, the Moon’s path is furthest below the ecliptic in Sagittarius. When it reaches this point, the Moon is as low as it can ever reach. Astronomers call this a "major standstill" (a minor standstill occurs when the Moon is at its highest above the ecliptic in Sagittarius).

Because this month’s full Moon merely skims the horizon, the positions where the Moon rises and then sets are at their closest together. Rising and setting points were extremely important to the ancient astronomers five millennia in the past, and were often literally set in stone. The central line of Stonehenge, for instance, points to the position where the Sun sets at the winter solstice.

When Stonehenge was constructed, we have good evidence that its builders were observing not just the pattern of the Sun’s rising and setting, which repeat every year, but also the more complex motions of the Moon. A rectangle of stones outside the main structure of Stonehenge – the so-called "station stones" – are aligned to point to the position of the southernmost moonrise at a major standstill.

In the Outer Hebrides lies an intriguing stone monument of about the same age. Calanais (also spelt Callanish) comprises a small stone circle with lines of stones radiating outwards. The most impressive of these stones form an avenue that runs roughly north-south, and is aligned with the Moon’s major standstill. If you stand at the end of this avenue on the night of the Full Moon this month, and look southwards, you’ll see the Moon skim the horizon over a curve of hills known as Cailleach Na Mointeach ("the old woman of the moors"), before setting directly behind the central stone circle.

These alignments show just how sophisticated these ancient astronomers were. They must have tracked the Moon’s motions over several 19-year cycles to establish how the pattern repeated, and to be confident enough to dedicate a huge amount of effort in constructing a mighty stone monument – at a time when the average life expectancy was less than 30 years.

If you’re in the Outer Hebrides this summer, Calanais is a must-visit. Also check out The Cailleach, The Moon & The Stones exhibition just down the road at Kinloch, Isle of Lewis.

What’s Up

This month, we are treated to not only the highest Sun in the sky, as we reach the summer solstice on 21 June, but also – on the night of 10-11 June – the lowest Full Moon not just of this year but for the next 18 years (see main story).

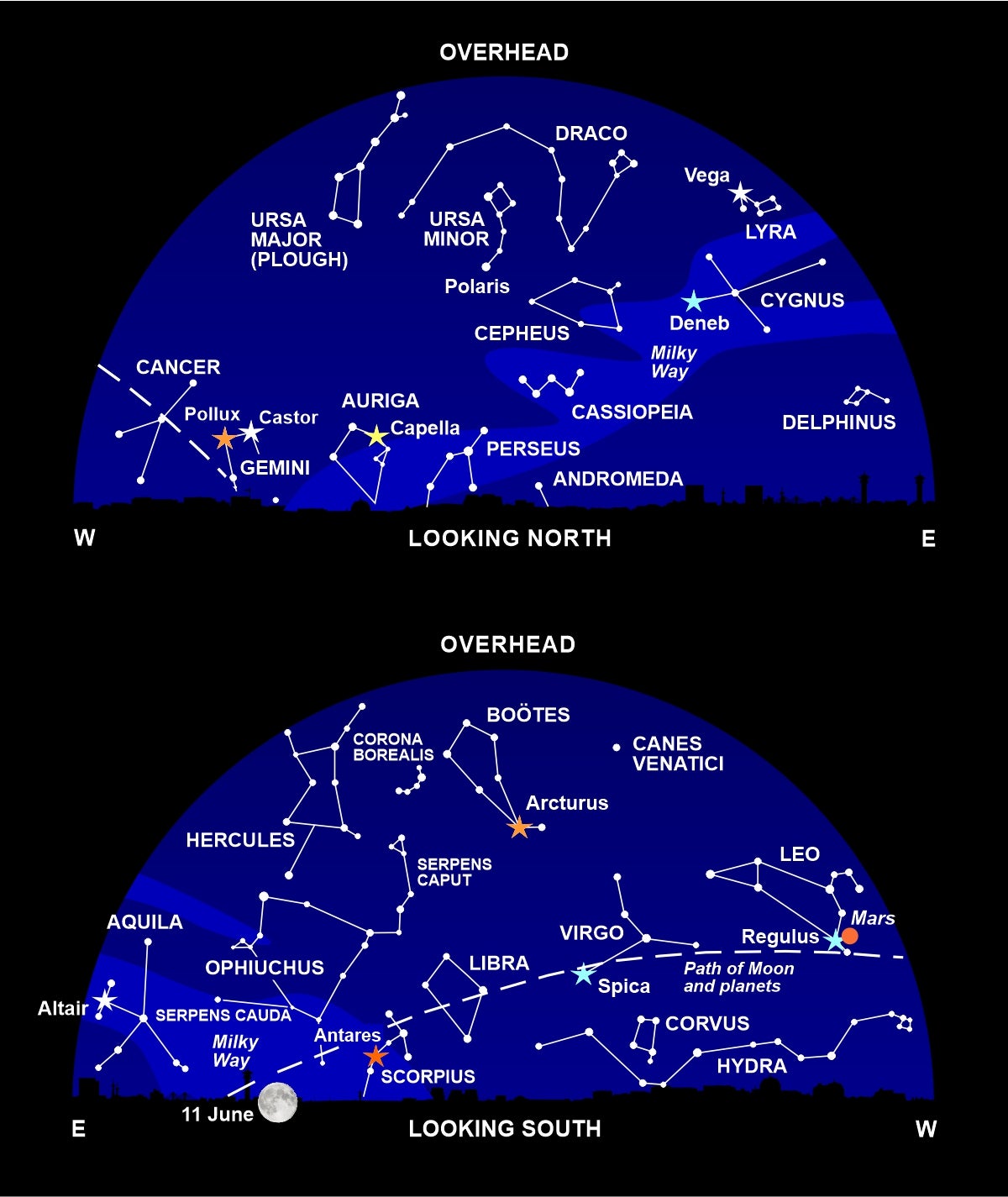

At Midsummer, the sky hardly gets dark for people in northerly climes, and it’s often easier to pick out the brightest stars rather than complete constellation patterns.

To the south, orange Arcturus is high in the sky, with the blood-coloured red giant Antares low on the horizon to its left. To the right, you’ll find blue-white Spica; and to the right again, over in the east, is similarly-hued Regulus, marking the heart of Leo, the lion. And just for this month, you’ll see that Leo appears to have a double heart, as Regulus is joined by Mars.

The Red Planet passes closest to the bluish star on 17 June. The two are currently about the same brightness, and the gorgeous colour contrast will be a treat to observe in binoculars or a small telescope.

A similar close encounter between Mars and Regulus in 1854 was immortalised by the Victorian Poet Laureate, Alfred Tennyson in his poem Maud. During a dream, the eponymous heroine ‘pointed to Mars/ As he glow’d like a ruddy shield on the Lion’s breast.’

The Moon passes between Mars and Regulus on 29 June.

During the second half of June, look very low on the north-western horizon to spot elusive Mercury: you’re best off using binoculars to see it against the twilight glow. On 27 June, the innermost planet lies to the lower right of the crescent Moon.

In the morning sky, you can’t miss Venus, shining more brilliantly than any star. There’s a glorious sight on the morning of 19 June when the crescent Moon hangs directly above the Morning Star.

Before dawn on 23 June, watch the Moon move in the front of the Pleiades – the Seven Sisters - and hide some of its stars.

Diary

6 June: Moon near Spica

9 June: Moon near Antares

11 June, 8.44am: Full Moon

17 June: Mars very near Regulus

18 June, 8.19pm: Last Quarter Moon

19 June, before dawn: Moon near Saturn

21 June, 3.42am: Summer solstice

22 June, before dawn: Moon near Venus

23 June, before dawn: Moon occults the Pleiades

25 June, 11.31pm: New Moon

27 June: Moon near Mercury

29 June: Moon between Mars and Regulus

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments