Hunger is war’s quiet executioner – and Gaza is the hungriest place on Earth

The UN has warned of catastrophic levels of food insecurity in Gaza, as well as declaring it the hungriest place on Earth. As millions of civilians are affected, Guy Walters looks at how hunger in conflict zones can kill more people than bombs or bullets ever do and how history will judge this period

There is perhaps no more primal weapon in war than hunger. Long before drones buzzed overhead and missiles lit up the night sky, armies resorted to siege and starvation to break their enemies. To restrict food does not just target soldiers, it also attacks the very foundations of civilian life – families, communities, children. And today, as the world watches the deepening crisis in Gaza, questions about the deliberate denial of food are again at the forefront.

It is abundantly clear, even from the Israeli government’s own statements, that access to food and water has been sharply curtailed in Gaza as part of a wider military campaign. Since Hamas’s brutal attacks on 7 October 2023, Israel has responded with a military campaign that includes what then defence minister Yoav Gallant called a “complete siege … there will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed”.

Civilians are now going hungry. The United Nations has warned of “catastrophic levels” of food insecurity, warning that Gaza is the “hungriest place on Earth” and is facing catastrophe, as aid continues to struggle to reach starving Palestinians. The president of the Red Cross has also dubbed Gaza “worse than hell on earth”.

The controversial US-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation announced late on Tuesday night it was temporarily shutting down operations in the strip after at least 58 Palestinians were reportedly killed attempting to access its distribution centres. Palestinians collecting food boxes have described scenes of pandemonium, with no one overseeing the handover of supplies or checking IDs, as crowds jostle for aid.

History tells us the military hunger game has a long and cruel lineage as a tool of war. Medieval warfare in Europe offers many cases of castles and cities denied supplies until desperation forced surrender. Take the siege of Rochester Castle in 1215, during King John’s campaign against rebellious barons. When siege engines and tunnelling failed to dislodge the garrison, John ordered that the defenders be starved into submission. Surviving accounts describe soldiers boiling leather for soup and gnawing on rats. Eventually, the castle fell not because of military defeat, but hunger.

Fast forward seven centuries to Leningrad (now St Petersburg) in the Second World War. From 1941 to 1944, Hitler’s armies encircled the city with the explicit aim of starving its population. “We have no interest in saving the population,” declared Hitler’s Directive No 1,601. Civilians were cut off from supplies and bombarded from the air. More than a million died –many from starvation, with reports of cannibalism emerging in the most harrowing months. Leningrad was not a military base; it was a city of women, children, and the elderly. And yet, hunger was wielded as a primary weapon.

Leningrad was not alone. During the “Four Days of Naples” uprising in September 1943, when German forces were retreating and Italian resistance surged, supplies to the city were devastated. Civilians scavenged ruins for morsels; children collapsed from hunger. When the writer Norman Lewis, then a soldier, arrived in Naples, he observed that it had become “a city so shattered, so starved, so deprived of all things that justify a city’s existence to adapt itself to a collapse into conditions which must resemble life in the dark ages”. Though the siege was relatively brief, it left deep scars and highlighted how quickly food insecurity can emerge in urban warfare.

One of the most infamous examples of strategic starvation comes from the British blockade of Germany during the First World War. The Royal Navy’s blockade, initiated in 1914, aimed to choke off not just materiel but foodstuffs. By 1918, estimates suggest that over 400,000 German civilians had died from causes linked to malnutrition and related diseases. The blockade was a central plank in Britain’s military strategy. While not aimed at extermination, its consequences for civilians were severe. After the war, the morality of the tactic was fiercely debated.

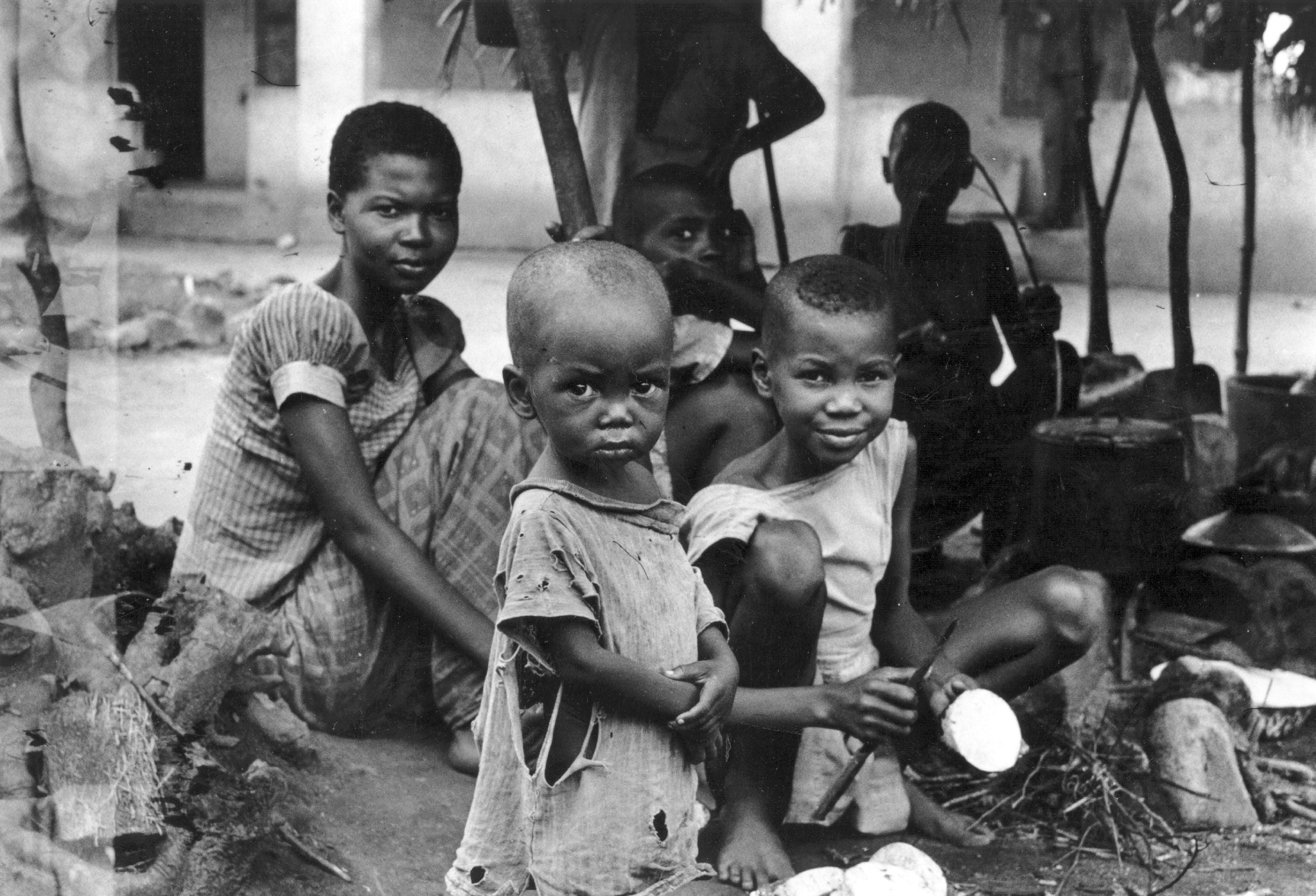

The Biafran war in Nigeria in the late 1960s provides another tragic example. As the Nigerian government sought to crush the Biafran secession, it implemented a blockade that resulted in widespread famine. Images of starving Biafran children – bloated stomachs and skeletal limbs – horrified the world and helped galvanise the humanitarian aid movement. The Nigerian leadership justified the blockade as necessary to end the rebellion. But for many observers, it became a symbol of cruelty: the deliberate starvation of a civilian population for military ends.

The siege of Sarajevo in the mid-1990s during the Bosnian war offers a more recent case. While not entirely cut off, Sarajevo’s population endured severe food shortages as Bosnian Serb forces surrounded the city. International aid convoys were often blocked or shelled. Civilians queued for bread under the telescopic gaze of snipers. The tactic was clear: squeeze the city until resistance collapsed. Food became leverage.

Meanwhile, Gaza is not the only place in the Middle East where people are going hungry or starving. The conflict in Yemen, where the Saudi-led blockade of ports controlled by Houthi rebels has led to acute food shortages, illustrates the complexities of modern hunger warfare. Human Rights Watch and the UN have criticised all parties in the war – including the Houthis – for using food access as a pawn. Yemen’s hunger crisis is among the worst in the world, and while the causes are complex, military interference in food supply chains has clearly played a part.

And now, Gaza. While a limited number of aid trucks have been allowed in, the volume is far below what is required to feed a population of some two million. Children are reportedly dying from malnutrition. The UN says that famine is “imminent”. Humanitarian agencies struggle to operate under airstrikes, and some have accused Israel of deliberately obstructing aid.

Israeli officials argue that Hamas embeds itself among civilians and that restrictions on aid are necessary to weaken the group’s military capacity. There is evidence that Hamas has diverted resources, and that the delivery of aid has been politicised by all sides. But a distinction must be made between military necessity and collective punishment. Under international humanitarian law, particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949) and Additional Protocol I (1977), the starvation of civilians “as a method of warfare” is explicitly prohibited. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court states that “intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare” is a war crime.

Whether that threshold has been crossed in Gaza is, ultimately, for lawyers and investigators to determine. In an opinion piece for the Israeli newspaper and website Haaretz, “Enough is Enough. Israel Is Committing War Crimes”, the former prime minister of Israel Ehud Olmert argued that recent operations in the Gaza Strip now have nothing to do with legitimate war goals. He wrote: “The government of Israel is currently waging a war without purpose, without goals or clear planning”, adding that the “pointless victims among the Palestinian population” were reaching “monstrous proportions” in recent weeks.

The issue, of course, is whether the starvation is “intentional”, or a “method of warfare” – or simply a horrifically unfortunate side effect of the conflict. The International Criminal Court has already announced investigations.

But what is not in question, however, is that the humanitarian toll on Gaza’s civilians is extreme. Food has become not just a human need, but a point of pressure – and history shows that when hunger plays out in war, the moral line is often perilously close to being crossed.

Wars are often judged by the images they leave behind – charred buildings, bomb craters, lifeless bodies. But hunger works in silence. It doesn’t explode or flash. It kills by degrees. Yet it may kill more people than bombs or bullets ever do. In the case of Leningrad, most deaths were from starvation, not enemy fire. In Biafra, bombs fell, but the famine stole far more lives. In Yemen, many thousands have perished – not from airstrikes, but from the slow attrition of hunger and disease.

Starvation is war’s quieter executioner. It affects the very young, the very old, and the already weak. It leaves scars that last for generations. It destabilises societies, fuels cycles of poverty and conflict, and haunts the conscience long after treaties are signed.

Humanitarian law exists not only to constrain how wars are fought, but to remind the world that even amid the ugliest conflicts, there is a line between strategy and atrocity. Starving people into submission may achieve short-term military objectives, but it does so by destroying the very idea of protected civilian life – a cornerstone of international law.

History is replete with examples of food used to subjugate, punish, and destroy. The outcome is always the same: civilians pay the highest price. And while the means may evolve – castles have given way to cities and organised supply chains – the tactic remains grimly familiar.

In the coming weeks and months, as diplomatic and legal processes unfold, the international community must reckon with the implications of hunger as a weapon. Food is not just sustenance; it is a right. To deny it is not only to wage war on armies, but on the very essence of human dignity.