The amateur detectorists who struck £12m in gold – and then stole it...

George Powell and Layton Davies could have walked away with a fortune when they uncovered a Viking hoard worth millions – instead, they became Newport’s most wanted. What followed was a chaotic tale of greed, clandestine treasure, and entire histories being written. David James Smith reports

On a June day in 2015, George Powell was the luckiest man alive. He had been metal-detecting in a field near Leominster in Herefordshire with his mate, Layton Davies. To put it kindly, George has been in a lot of trouble in his life. He had amassed 22 convictions for 55 offences, such as burglary and deception. He was quite vain about his appearance. He had several elaborate, quite visible tattoos.

In one photo, he wears reflector sunglasses and an unbuttoned white shirt that reveals his tanned upper body. Layton Davies, by contrast, had been a model metal detectorist. He had almost always done the right thing. He was a school caretaker from Pontypridd. A grandfather. Perhaps his mistake was agreeing to go to Leominster with George. Layton drove, taking George in his VW Campervan on the 110-mile round trip.

We may never know why they chose that particular field. I haven’t calculated the odds, but it is fair to say they were incredibly long. There have only ever been a handful of discoveries on the scale that George was about to make. After some hours of detecting and the usual nothing – ring pulls, bits of tractors and the like – his detector went off. Beep, Beep.

George stopped and began digging. Layton joined him. There, beneath the surface, they struck gold. Not just gold. A lot of silver, too. A 1,000-year-old hoard of Anglo-Saxon coins and jewels. It must have been a Eureka moment of some magnitude.

What they had stumbled on was a Viking’s stash, buried – and we can be quite precise about this – in the year 879. We don’t of course know who buried it or why, we just know that a great heathen army (of Vikings) had passed through the area that year. One among them must have wanted to hide their trophies, which were no doubt the result of an orgy of pillaging. The unlucky Viking may have intended to retrieve them later, but never made it back. Instead, those coins and baubles remained there beneath the surface for 1,136 years – until George unearthed them. Not so much a Norse marauder as a Newport buccaneer.

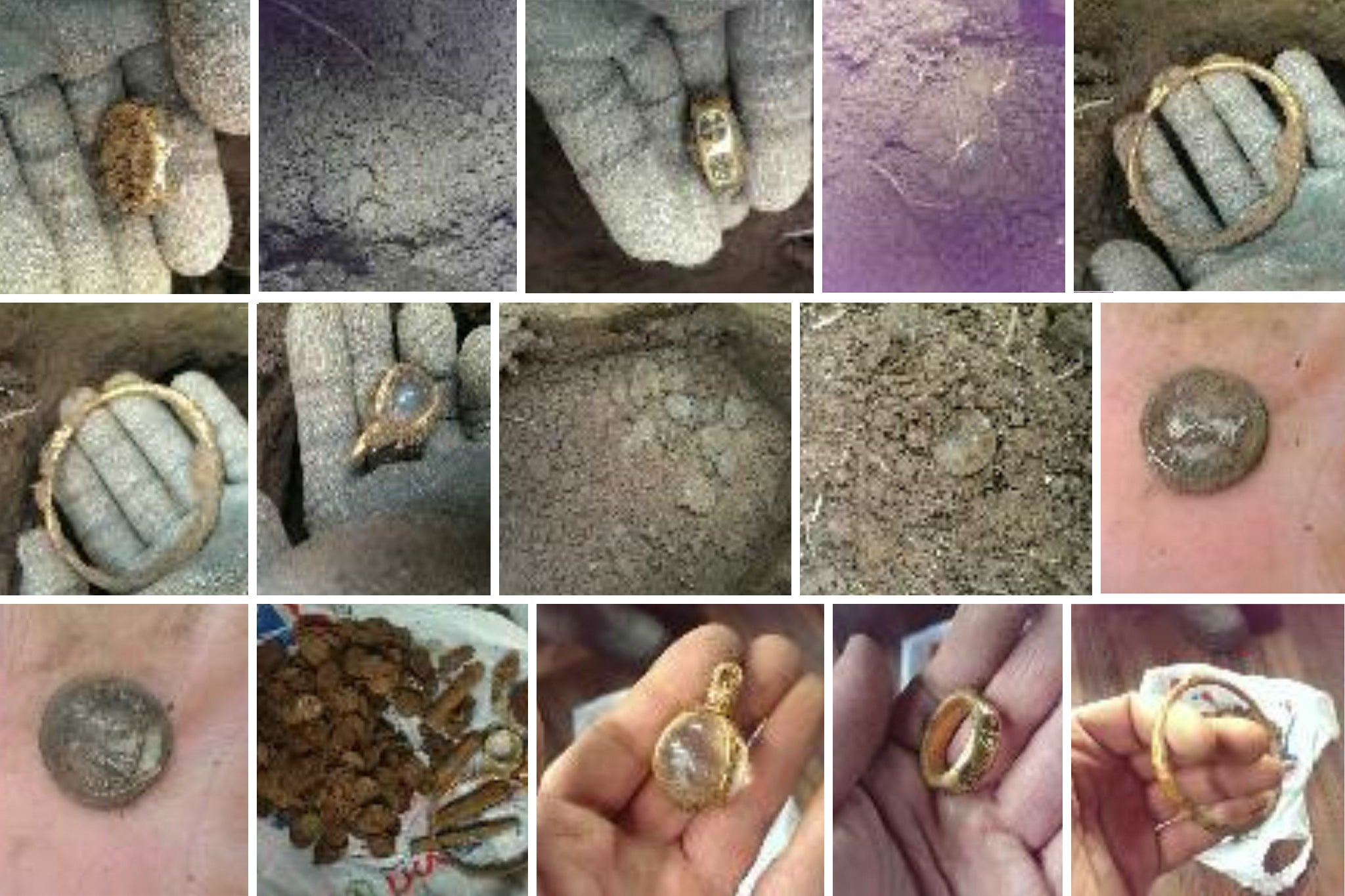

We only know what George and Layton found that day because they took a photo of it all, heaped unceremoniously on top of a Tesco carrier bag. The photo was eventually analysed and recreated with small coin-shaped discs by Dr Gareth Williams, an expert consultant in both Viking and mediaeval coins, who was then working at the British Museum. He estimated approximately 300 coins. The value was as much as £12m.

But, it was difficult to be sure because the hoard had vanished. While the pair “cleverly” deleted the photo when they were trying to disguise their tracks, it did not take the police long, once they began investigating, to undelete it. To say that the evidence was damning would be an understatement.

As George and Layton well knew, there are laws that determine what you must do when you find buried treasure. Finders are not keepers. Treasure belongs to the state, and the 1996 Treasure Act says you must declare it to the coroner within 14 days.

But that’s okay because, ordinarily, it will be valued, bought by a museum, and the proceeds shared between the finder and the owner of the land.

Normally, a detectorist seeks permission from the landowner before detecting in their field. They make a deal to share any proceeds, usually a 50/50 split. George had sought permission, but for a different field and a different tenant. I think he was too intimidated to approach the owner of the field where he found the hoard. He called him the lord of the manor, because the owner was actually a nobleman – Lord Cawley.

George was the luckiest man alive. If only he and Layton had done the right thing, they would likely have become millionaires, and Lord Cawley would have done pretty well out of it too (even better than he eventually did). If only.

Instead, unfathomably, they decided not to hand in the hoard but to steal it and sell it themselves. And as you might imagine, a whole trail of chaos, the story of the new BBC Fool’s Gold podcast, which I helped to create, ensued.

Initially, George and Layton could not contain themselves; they boast-posted some pictures of the coins on a Detecting Wales website and took them to a coin dealer, Paul Wells, at an antiques emporium in Cardiff. They were giddy with excitement at that meeting. George had to be told to calm down and “shut the f*** up”. Wells made a mistake and took a small handful of coins for safekeeping. He ended up arrested alongside George and Layton and a fourth man, Simon Wicks, who also had the misfortune to know George of old.

Wicks met George at a service station on the M4 and then went to a Mayfair coin dealer with some incredibly rare coins which he denied George had given to him at the meeting. The patina of the coins precisely matched others that were recovered from the hoard.

When they realised the authorities were on to them, George and Layton made a show of doing the right thing and went to report their discoveries to the finds liaison officer at the National Museum of Wales. They handed over three beautiful pieces of gold jewellery – and two coins which they said was all they had found. That, of course, was a lie.

It took West Mercia Police four years to unravel the facts and bring the case to trial at Worcester Crown Court. In 2019, the four men were lined up in the dock accused of various offences related to the theft of the hoard. Kevin Hegarty, the KC who prosecuted George and Layton and two others at the eventual trial, observed that it was as if the hoard had a bewitching effect on all who encountered it.

In his evidence, Dr Williams described the great historical significance of the hoard, notably the almost unheard-of coins depicting two Saxon Kings side by side – Alfred and Ceolwulf – indicating an alliance previously unknown to historians. The coins were rewriting our national history. Each one of those so-called two emperor coins was worth upwards of £50,000. No one could say how many were in the hoard because no one other than George and Layton had ever seen it all.

As was his right, George never gave evidence at his trial. Layton did, however, and attempted to claim they had already owned the coins and merely taken them to the field in a rucksack and laid them out on the Tesco bag to claim false provenance.

Unsurprisingly, the jury did not swallow that version of events, and all four men were convicted. All but Wells went to prison. A family man and hitherto reputable dealer, he had suffered considerably with his physical and mental health and received a suspended sentence. George served the longest prison term of six-and-a-half years.

But that was not the end of his troubles. The law assumed he had the benefit of the coins and subjected George and Layton to Proceeds of Crime confiscation orders of £600,000 each. If they did not pay (or return the missing coins), they would serve a further five years and three months in prison.

Evidently, they did not have the money or the coins – for who in their right mind would want to go back to prison for another five years if they could avoid it?

Layton accepted his fate last autumn and returned to jail. George has been at large ever since, ducking and diving. When he should have been in court, he went on holiday to Turkey and met a new girlfriend, Tracey, but that relationship did not make it to Christmas.

In November, Gwent Police put a wanted poster of George on its Facebook page. George began commenting on the post as George Dennis Blackbeard. He said he did not like the mugshot they had used, as it had been taken when he had a hangover. He made fun of the police.

Seeing the posts, Holly Morgan, then a trainee journalist at the South Wales Argus, reached out to George and he responded. Morgan knew nothing about the background of George’s case and took his protestations of innocence at face value. He promised her the interview of her career, with him.

For the podcast, we began working with Morgan to try to talk to George, hoping to finally find out what he had done with the rest of the coins, even though, he said, he would take that secret to his grave.

There were (quite properly) hand-wringing conversations about the ethics of interviewing a suspect on the run. Arrangements were made and cancelled. George was arrested and released after a few days in a northern prison. (Gwent Police reissued their wanted notice while he was actually in custody.)

George said he was going home to Newport to get a fresh trim and hoped to meet Morgan. He sent her a video of the hotel room where he was staying and proposed meeting for a drink in the bar opposite. But she was focused on an interview that we would both attend. At one stage, George agreed to talk – but only if we bought him a new suit and a metal detector to use as props for his portrait photos.

We haven’t met yet. Perhaps we will end up visiting him when he finally returns to prison. There is so much for George to explain, not least the mystery of the missing coins – with potentially as many as 250 still out there somewhere.

In 2023, two men, Craig Best and Roger Pilling, were convicted and imprisoned for five years after attempting to sell just over 40 coins from the hoard to an American dealer. Best had been arrested in the bar of Durham’s Royal County Hotel while trying to sell three sample coins to a broker for the US buyer. In fact, the broker was an undercover detective and Best and Pilling had been the victims of a police sting. They claimed they had bought their coins from “John” at a service station.

Was “John” in fact George?

I have tried to put myself in the shoes of George Dennis Powell, but it is not easy.

I wondered how he felt when Lord Cawley received the entirety of the proceeds of the sale to the Hereford Museum of the small part of the hoard that had been recovered. The hoard will form the centrepiece of the museum’s big refurbishment.

The museum paid exactly £776,250 (the sum settled by the Treasure Valuation Committee) and the whole of it went to Lord Cawley. He told me it was like winning the lottery.

Surely, George has thought about that and what might have been his, if he had done the right thing.

David James Smith is the associate producer of Fool’s Gold, an eight-part BBC Wales podcast narrated by Aimee-Ffion Edwards for BBC Sounds