My mother and father were Cold War spies – now I hold the family secrets

Living in a Secret Intelligence Service camp and cycling past guards every day seemed like a normal thing to Alistair Wood. It was only in his teenage years that a more colourful picture began to emerge – one that involved espionage, an enigmatic father and ‘an incident in Helsinki’...

When I was 10, I received – quite unexpectedly – a punch in the face. I was standing in a suburban London playground, answering what appeared to be a perfectly normal question; a very simple question. “Where’s your dad?” the boy, as small as me, asked. I told him the truth as I knew it: that my father was in Vietnam. Apparently it was not a satisfactory answer. In early suburban London, fathers were accountants or train drivers, and the like.

They were not “in Vietnam” at the height of the war. Not unless you wanted a black eye and a reputation as a liar, anyway. I thought to myself, “Well. If they don’t believe that, they’re not going to believe the rest of it.”

It was ingrained in me from a very young age not to tell anyone about the goings on in our house – perhaps everyone thinks their family is unique, but there was definitely something different about mine.

Even when I was a young kid, I was aware of this intriguing backdrop but, really, it was all borrowed interest – my childhood in London looked like a collection of half-glimpsed realities. I knew my mother was slightly dodgy, for instance, though it was never fully explained.

My older brother and I would watch curious belongings turn up at the house every now and again without explanation – bits of radios, the occasional gun, stuff like that. Growing up, people you might not expect told me, “Your mum’s a remarkable person, you know, you don’t seem to realise this”. Perhaps I didn’t in the way they did, not yet anyway. My father, however, remained a bit of a mystery.

He had always been absent; he’d “skeddaddled off to another country” as my mother bluntly explained – that much was fact. My mother brought me up and, later, my stepfather – a lovely man – and it wasn’t until I was 13, when we moved to a British Secret Intelligence Service camp that a bigger, much more colourful picture began to emerge. Naturally, it was a bit bewildering; I’m not sure I fully understood where we’d moved to, though I knew it was far from being Butlins. The first year or so wasn’t great – suddenly I’d gone to live in this enclosed environment where I wasn’t allowed to make friends, and things were all a bit awkward.

My mother, who ostensibly worked as a secretary, would tell us to keep away from the windows because ours was the only occupied house – we didn’t want to attract any more attention. My stepfather ran the internal workings of the camp, so he had to live on the premises. I was a small boy on a bike, whizzing around the place, that everyone eventually got used to seeing around. Sometimes I would crouch behind my handlebars and sneak out without anyone noticing, which would give the guards a bit of a problem.

Looking back, it was great fun; a bit monastic. There were no other children whatsoever, but it was filled with colourful characters – many of whom, I’d slowly learn, had worked with my father at one time or another for better or, normally, for worse.

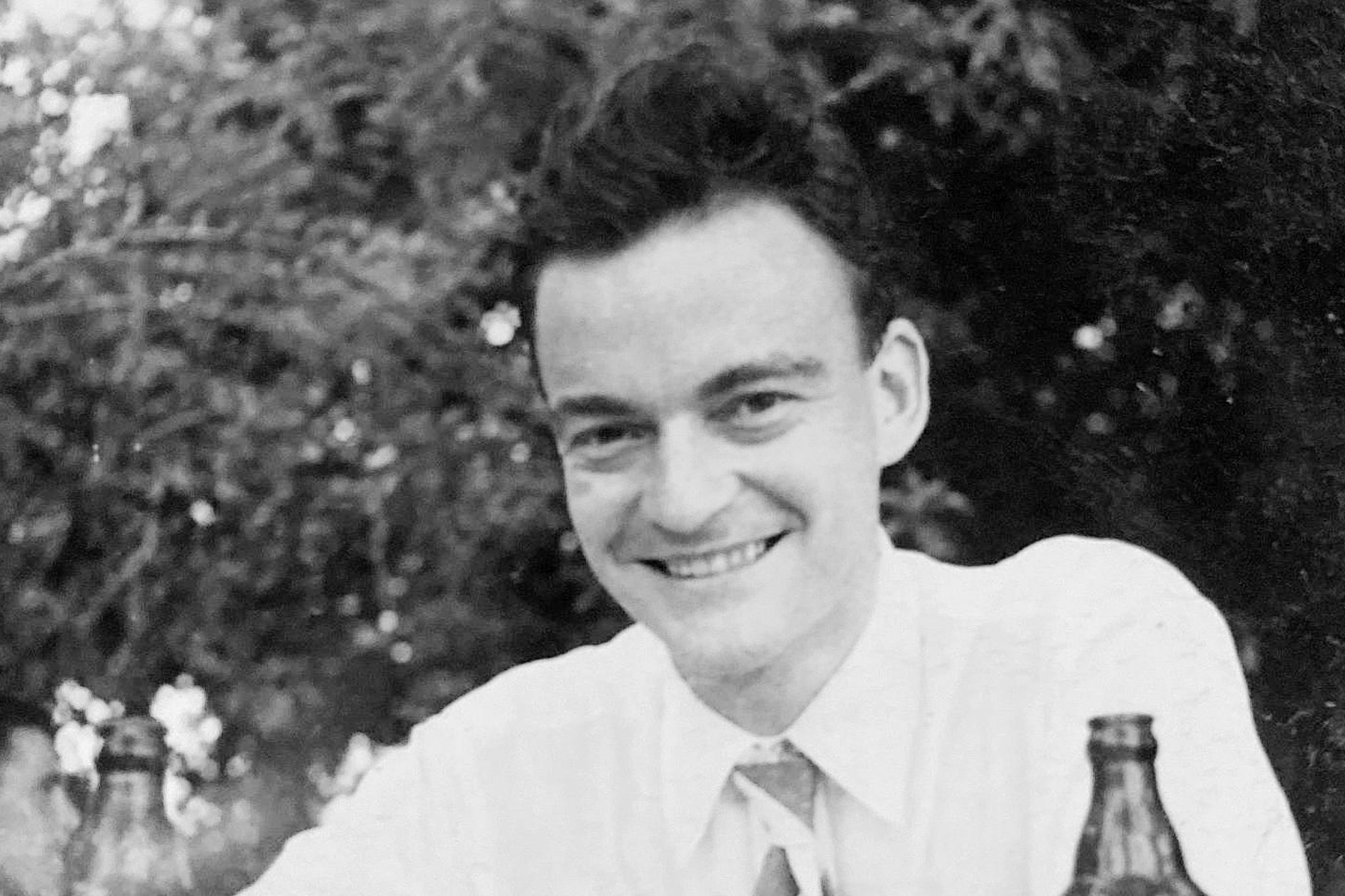

Up until then, I really hadn’t known anything about my father at all. Of course, I’d known of him. But here I was referred to as the son of JB Wood – John Bryan Wood, or JBW as he was known by one and all – which was slightly news to me, in a funny sort of way. A new commanding officer called John Wyke revealed a bit more: he was a great fan of my father and told some stories about him, though to me he mostly remained a distant enigma; a glamorous figure and, quite plainly, a notorious spy.

Others weren’t so keen. My father, it seemed, was a divisive figure. He was a spy, yes – but more importantly, he was an unreliable one. At least, that was the version that floated through the corridors. He’d been kicked out after an “incident” – an attempt on his life, as my mother explained – in Helsinki, which was explained to me (rather unconvincingly) as the result of a blown cover. Even then, I knew that was nonsense.

The truth, as later revealed in whispered conversations with the great Harold Shergold himself, was far more damning. My father was one of the few people who knew about an operation regarding the M16 tunnel under East Berlin, and when it was betrayed, suspicion fell squarely on him.

Of course, it turned out years later that it hadn’t been my father. But by then, of course, he had reinvented himself; he was very good at it. He popped up in Saigon as head of the UN during the Vietnam War. Later, he emerged in Bosnia, helping during the war. It was there he was buried with full honours, mourned by thousands in attendance at his funeral – as I ruefully said to my wife, “Christ, he’s close to sainthood”, and he was.

But, saint or not, it’s my mother that I suppose really emerges as the hero of the story. She too was a spy, though she would never have agreed with the term. She was, in her quiet way, quite formidable. I only began to learn this after inheriting a cache of her letters, miraculously preserved by a great aunt. Suddenly, those comments from teachers began to make sense. This was a woman who was unflappable in nature, single-handedly bringing up two children, drinking soldiers under the table one night and walking into East Berlin as a decoy the next.

You’ll be surprised to hear that I didn’t take up the family line of work – rather, after my brother and I turned 18 and were responsible for navigating our own way somehow, I ended up working in the London advertising boom of the 1980s and 1990s. But it has been an adventure in my own life to sit and write about all of this, though admittedly rather exposing. Most of my friends had no idea about any of it; even my own children were taken aback. I suppose it’s not every day you learn your grandparents were spies.

The book – My Family and Other Spies – emerged not out of a desire to boast, but out of a need to bear witness to something utterly unrepeatable. No one will grow up in an SIS camp again. No one will ride their bike past snipers and ex-paratroopers. And no one, I suspect, will again have quite such a gifted but catastrophically flawed father.

If there’s one thing I hope anyone reading it takes from the story, it’s this: sometimes, the truth is stranger than fiction, but quieter. It sits in the back room, stirring tea, and pretending it never happened. And if you’re lucky, you inherit enough of it to write the bloody thing down before the rest forget.

As told to Zoë Beaty

My Family and Other Spies, by Alistair Wood, is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments