A philanthropist’s art collection that shows how Goya anticipated Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne

Romantics, Realists, Impressionists and Post-Impressionists mingle in a show that sheds light on their interconnectedness

Is there much further mileage in Impressionism? There’s certainly no shortage of public interest, judging by the huge response to the Courtauld’s recent Monet in London exhibition and the National’s just-closed Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers – the most popular show in the gallery’s history. But what are the chances of an exhibition of the greatest hits of a single Impressionist collection – however stellar – providing major new insights into this well-trodden territory?

At first sight, the Oskar Reinhart Collection (usually housed in Winterthur, Switzerland), feels almost the mirror image of the Courtauld. Both were created in the early 20th century by wealthy businessmen with a philanthropic bent and an obsession with Impressionism. With the former’s handsome premises near Zurich under refurbishment, a group of key masterpieces has arrived in London for a show that should perfectly complement the Courtauld’s stunning permanent Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collections.

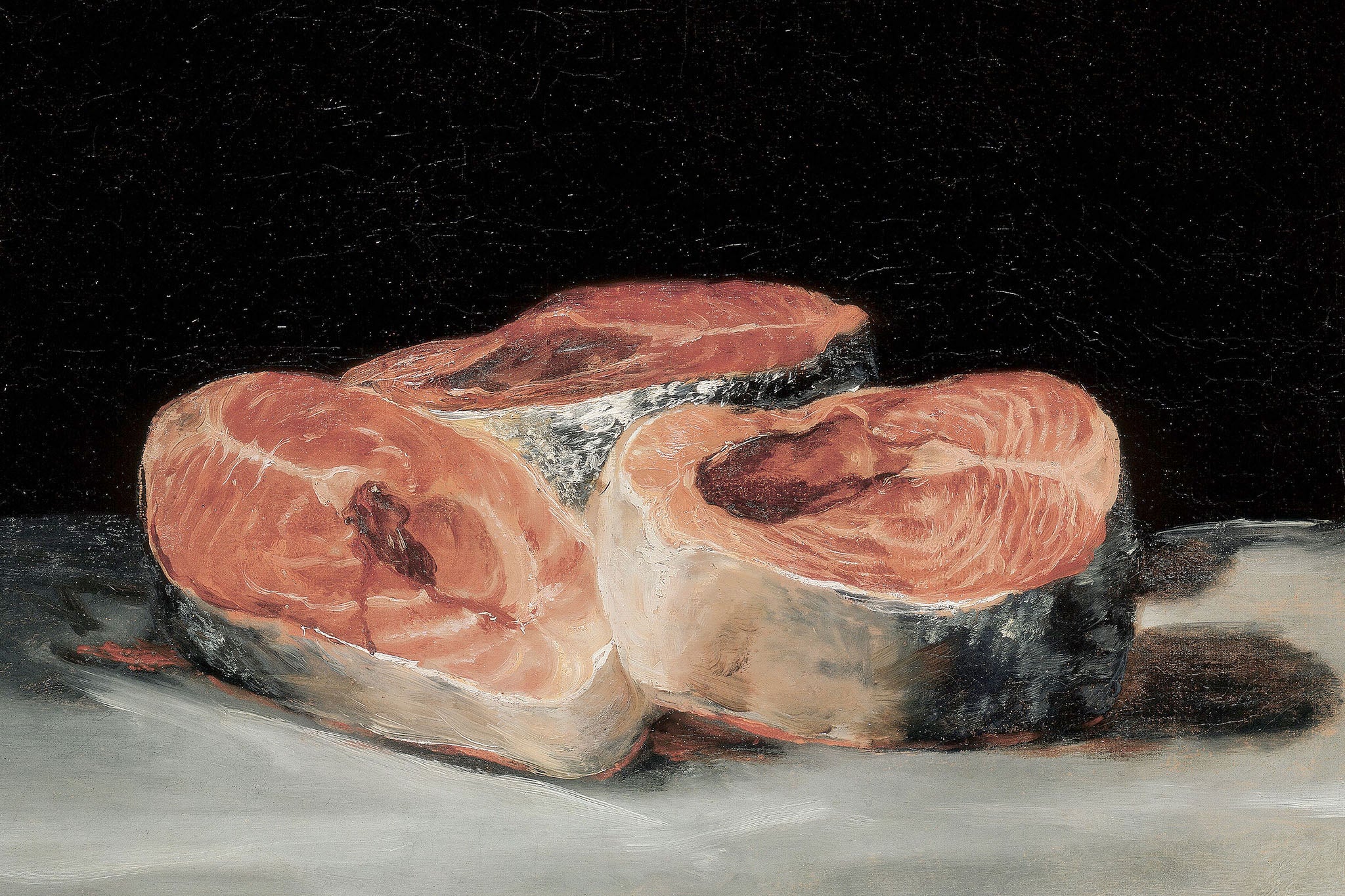

If the inclusion of Goya in the show’s title feels like a rather clumsy attempt to gild the lily by yanking in another mega-name, a group of early 19th-century paintings at the start of the show proves otherwise as they deftly set up the glories to come. Goya’s bluntly matter-of-fact Still Life with Three Salmon Steaks (1808), a mound of oily pink fish against a dead black background could pass for the kind of determinedly mundane still life painting the great Impressionist pioneer Edouard Manet was producing 70 years later.

Meanwhile, Theodore Gericault’s A Man Suffering from Delusions of Military Rank (1819), one of a series of haunting portraits of the mentally ill by the great Romantic painter, feels disconcertingly modern in both its subject and unflinchingly direct treatment. And a turbulent seascape by Gustave Courbet, leader of the opposing Realist tendency, compounds the sense that far from being a bolt from the blue, as we tend to imagine, Impressionism was the natural outcome of a number of existing trends.

When it comes to the Impressionists themselves, nearly every work seems to offer a surprising twist. We tend to think of Cézanne as a Post-Impressionist who paved the way for Cubism and other 20th-century breakthroughs. Yet his magnificently physical Portrait of Dominique Aubert, with its rich blacks, pinks and whites larded on with a palette knife, dates from 1866, pre-dating Impressionism proper.

And I doubt if anyone seeing the large, bold and admirably unfussy Lily and Greenhouse Plants (1864), which gives us, very plainly, exactly what the title says, would imagine it was by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, generally seen as the most soft-centred of the Impressionists. There’s a privileged sense of looking in on some of the world’s most famous artists before they were Impressionists.

While there are no surprises in Monet’s The Breakup of Ice on the Seine (1880), the reflections of poplars among shards of ice are so vividly evoked in the sketchiest of paint strokes that you can practically feel the chill air flooding off the canvas. If none of us are currently in need of any more chill air, there’s a palpable warmth in the orange-tinged walls and earth in Gauguin’s Blue Roofs (Rouen) (1884). The bad boy of Post-Impressionism is captured at the moment when he’d given up his day job as a stockbroker and was evolving his own symbolically charged approach to colour.

Cézanne’s Still Life with Faience Jug and Fruit (1900), a magnificent example of one of his monumental late still lifes, draws us into the artist’s preoccupation with simple objects which is so intensely, even transcendentally focused that it seems to blot out the rest of reality. Yet it’s impossible to look at the adjacent painting, Van Gogh’s deceptively serene The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles (1889), without it bringing to mind the tragic breakdown that had brought the artist there.

While there were a number of these perplexingly tranquil garden scenes in the recent National Gallery show, here we’re also offered a rarer work: a view of the interior in The Ward in the Hospital at Arles (1889), showing a group of his fellow inmates slumped around a stove. While the wall texts refer to a sense of “unease and imbalance” in the upward tilting perspective between the long rows of beds, I was struck more by a sense of heartrending stoicism as Van Gogh seizes one of his last opportunities to record the physical world he loved so much.

The show’s poster image, Toulouse-Lautrec’s The Clown Cha-U-Kao (1895), showing a faux-Chinese nightclub performer arm-in-arm with her girlfriend, provides such a wonderfully vibrant glimpse into the netherworld of the Moulin Rouge that it made me want to punch Baz Luhrmann for making such a caricatured travesty of a film about it. And if Edouard Manet can feel, for all his huge importance as an innovator, a touch stiff and formal as a painter, the bohemian figures in his Au Café (1878) look so tangibly alive you could almost climb into the painting to join them for a beer.

This modestly scaled exhibition may be an aside in the greater conversation surrounding Impressionism, but it’s one that provides vivid and often surprising glimpses into that now-distant time and world at every turn. It made me fall in love with this great moment in art all over again.

‘Goya to Impressionism – Masterpieces from the Oskar Reinhart Collection’ is at the Courtauld from 14 February until 26 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments